Prologue (an epic)

In civil history, we consult titles, we research medals, we decipher ancient inscriptions in order to determine the time of human revolutions and to fix the dates of events in the moral order. Similarly, in our history—that is, in your history—it is necessary to excavate the archives of the world. To draw old monuments from the entrails of the earth. To collect your debris. To reassemble into your body all the indices of change. This is the only way to fix points in the immensity of space, and to place a certain number of milestones on the eternal route of time.

And so. You are an American mammal.

You have a personal formula for a life of continual enjoyment and action. You say: it is sweeter to vegetate than to live, to want nothing rather than satisfy one's appetite, to sleep a listless sleep rather than open one's eyes to see and to sense.

You say: let me consent to leave my soul in numbness, my mind in darkness, never to use either the one or the other, to put myself below the animals, and finally to be only a mass of brute matter attached to the earth.

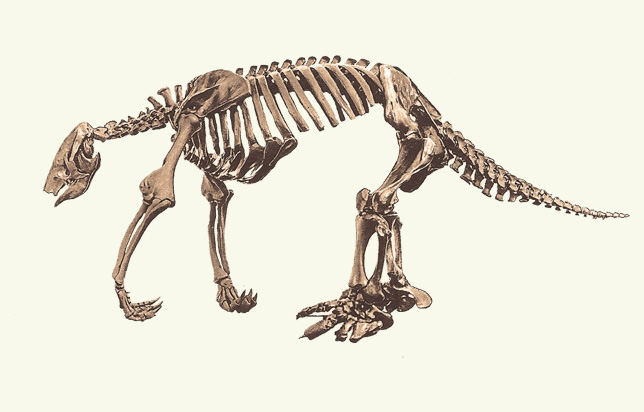

You have read somewhere that American mammals must be smaller than their Old World counterparts (rhino, giraffe, and tiger larger than tapir, llama, and jaguar, for example) because the heat is in general much less in this part of the world, and the humidity much greater. You are not chagrined at this charge of lesser stature. You accept the sloth—your sloth—in name and size and shape and description. You call it Megalonyx jeffersoni.

You say:

Whereas nature appears to us live, vibrant, and enthusiastic in producing monkeys, so is she slow, constrained, and restricted in sloths. And we must speak more of wretchedness than laziness; more of default, deprivation, and defect in their constitution. No incisor or canine teeth, small and covered eyes, a thick and heavy jaw. Flattened hair that looks like dried grass. Legs too short, badly turned, and badly terminated; no separately movable digits, but two or three excessively long nails.

Slowness, stupidity, neglect of your body, and even habitual sadness result from this bizarre and neglected conformation. No weapons for attack or defense; no means of security; no resource of safety in escape; confined, not to a country, but to a tiny mote of earth. The tree under which you were born. A prisoner in the middle of great space.

Everything about you announces your misery. You are an imperfect production, and scarcely having the ability to exist at all, you can only persist for a while, and shall then be effaced from the list of beings. You are the lowest term of existence in the order of animals with flesh and blood. One more defect would have made your existence impossible. Then let us say that it is sweeter to vegetate than to live, to want nothing rather than satisfy one's appetite, to sleep a listless sleep rather than open one's eyes to see and to sense. Let us consent to leave our soul in numbness, our mind in darkness, never to use either the one or the other, to put ourselves below the animals, and finally to be only masses of brute matter attached to the earth.

One (a fiction)

Somewhere in Argentina, 2009, a man falls in a pit between two rows of corn (or if you like, in Holland between rows of daisies, 1971). First he falls backward stiffly, as he imagines one must when shot from the front. Looking before him at the sky, curtained on the sides by yellowing stalks that are dry from lack of rain, he thinks to himself that it is too neat: one does not fall parallel, one must crumple or be thrown across impediments of various kinds.

He stands up. He tries again, this time letting his torso be twisted by the impact of the bullet (he imagines his father shot through a lung or in the heart; he can not bear the thought of a bullet to the head). He lands among the corn on his forearms, which serve to shield his face. Better, he thinks, but lacking in abandon.

He tries a third and fourth time; many times, buckling at the knees or locking them, eyes closed or open, and exhaling with iterations of yelps and cries that bear the phonic mark of words.

Na!, he says.

Ulp!

He wonders who dragged the body to its grave (a commander? a grunt? thirty years ago? thirty-one?) but then realizes the grave must come first, and the death topple into it: no one would have pulled at the dead man. Murder and disappearance must be one act combined. He sets to digging.

Some hours later he resumes the practice of falling, tending to land hard on his seat before the impact of elbow, scapula and head. The jolts make his eyes water. He blows liquid and dirt from his nose, wipes the stuff on a rock on the wall of the trench, and from there looks upward at the sky, now bounded on all four sides: a cinemascope of clouds.

But who will fill this grave, he thinks suddenly; who will heft dirt and shovel a hundred times, then tamp the edges?

The sea!, he remembers: the sea fills itself.

Two (a moving image transposed)

Imagine: a tent of velvet, matte and dense, as big as a pond; a platform up high; a figure in sequins, sparkling fuchsia, defined more by its movement than by its shape (which is a perfect shape, perfectly symmetrical).

The figure propels forward off the platform and then, as in sport, somersaults and twists, only to be brought downward. It is a controlled fall but a fall nonetheless.

The ground is velvet. As it eats light so it eats the body. There is no impact. The sequence repeats: the acrobatic descent of a body and its eclipse. The sequence repeats.

Three (a work of research, occluded and falsified)

Born a subject of the British Empire and so the Anglosphere, you were named Wilfred despite the place of your birth, now known as Uttar Pradesh, then known as the North Western Provinces of India. You were moved to Hertfordshire at a young age to attend Bishop's Stortford College, a non-sectarian public school founded by Evangelical Noncomformists about thirty-five years before your arrival there. Your teacher was one Mr. F. S. Young, and your classmates likely included the painter Percy Horton.

Three months shy of your twentieth birthday you entered into military service, attaining the rank of lieutenant and then captain within the span of a year, during which you commanded a tank corps along the Hindenburg line in France. For your efforts in the Second Battle of Cambria, including your capture of enemy tanks and your firing of a Lewis Gun to great effect, you were awarded both a Distinguished Service Order and the Croix de Chevalier.

After the war you moved to London to study history and the burgeoning field of psychoanalysis, the first at Queen's College London, the second at the Tavistock Clinic. Your training analysis was foreshortened in 1938 by the war, but not before you were brought into contact with an Irish playwright with the given name of Samuel, whom you counseled through problems with creative stasis, anxiety and sexual preoccupation. You served in the Royal Army Medical Corps, notably at Northfield Hospital, where you initiated various experiments related to both group behavior and the treatment of traumatic stress.

Upon return to London you initiated a training analysis with a follower of Freud known for her theory of object relations, and went on to author a series of influential papers that conceived of psychoanalytic concepts in mathematical and schematic terms. Many years later you abandoned this work for a more intuitive approach.

After living for ten years in Los Angeles, where you still exert an influence over the psychoanalytic community, and where one of your students—my own analyst—still practices, you died in London. Ten years later your daughter, named Parthenope after the siren of Greek mythology, distraught with unabated grief over your death and a undistinguished career as an analyst herself, piloted her car into a tree.

Four (a monologue)

I am splenetic and unhinged. I think out loud so as to quiet my thoughts. I talk to rid my gut of a suffocating gas, a noxious stuff that hangs in the air, irrespective of audience. I rail for hundreds of pages across dozens of novels through the pain of lung disease and in never-ending paragraphs to the limits of the printed word. (Gutenberg would be at a loss.) I am a monster, and I say to you that it is altogether nothing but a survival skill, never lose sight of this fact: it is, time and again, just an attempt—an attempt that seems touching even to our intellect—to cope with this world and its revolting aspects, which, as we know, is invariably possible by resorting to lies and falsehoods, to hypocrisy and self-deception. Yes. I avoid certain words (aslant, sausage, Auschwitz, Crimean wine...) but avoidance is not so much a perjury as an attempt. I attempt despite the pain, in the guise of artists and authors and musicologists, of losers and scholars and Geistesmenchen; I attempt, that is, until the pain is like a sea or a pit in the ground, swallowing all sense and will. Having had attempted, I am pluperfect and continuous. (Afterall, this is the age of the monologue.) I speak now from beyond to proclaim that my death was a suicide, it was ineluctable, it may have been hastened by my brother a doctor and the executor of my will but still it is mine to name, still mine even now.

* The prologue of this piece takes liberally from Epochs of Nature by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. It was originally written for Bizarre Animals, a site-specific exhibition of art at the Harvard Museum of Natural History in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in April 2011. For that show, the prologue and section one were pre-recorded by an actor and amplified in the Great Hall of Mammals. A different version of sections one through four were also published under the title Four Deaths, Self-Inflicted in Material Issue Two in 2010 by Material Press.